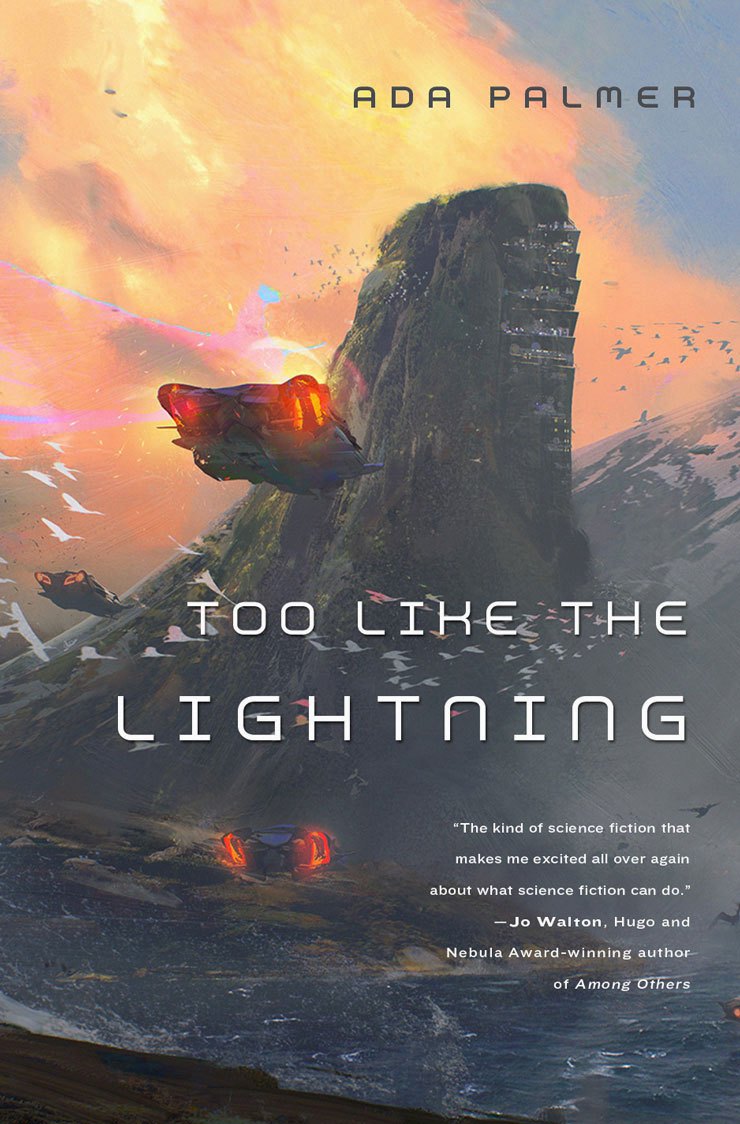

Sami Sundell reviewed Too Like the Lightning by Ada Palmer (Terra Ignota -- Book 1)

Review of 'Too Like the Lightning' on 'Goodreads'

5 stars

I'm annoyed by this book.

It starts with a simple scene: priest Carlyle Foster goes for a visit in Saneer-Weeksbooth household and runs into Bridger. There are a couple of things in this meeting that are peculiar.

First of all, it's year 2454 and everyone is connected and tracked through a device called... Well, tracker. Except for Bridger. He has one, but it doesn't track anything. Even though he's inside Saneer-Weeksbooth house, only Thisbe Saneer and servant Mycroft know about him. Officially, Bridger doesn't exist.

The second thing? It seems Bridger is a god. If he can imagine something, he can create it. Oh, and in 2400s religion is a taboo, so Carlyle Foster isn't a priest but a sensayer - sort of a theological therapist.

Despite meeting a god in the first page of the book, Bridger isn't really the focus of the story. The plot follows a theft of a newspaper article, but that isn't really the focus either. Instead, the theft is an excuse to follow the lives of the rich and powerful of this brave new world. Here, our guide and narrator is Mycroft the Servicer.

Mycroft has his own curiosities: he's a big fan of French Enlightenment philosophers, and for some reason or another decides to tell the story using 18th century English. This causes all kinds of confusion.

You see, in 24th century, people have gotten rid of war, nation states, religion, and gender. Since Mycroft talks in 18th century terms, he ends up using gendered pronouns, but instead of set rules he uses biology, behavior, looks, profession and societal standing to decide who to call 'he' or 'she'. Every time a new person enters a scene, there's a big chunk of text describing why Mycroft chose the pronoun he ended up using for that particular person. Occasionally, he argues with an imaginary reader as well, because apparently otherwise it would be too straight-forward.

Now, Engligh isn't my native language, and Finnish doesn't have gendered pronouns, so no matter what the pronoun used, I usually get used to it fast. In this case, though, (binary) gender is brought up time and time again, and it starts to get in the way of the story.

Of course, it's also part of the story, but the multi-layered anachronism that is used to highlight it seems contrived and starts to get annoying.

So, I'm at times annoyed by the book, and at times I'm amazed by the sense of wonder. Reading it is a bumpy experience, and I'm not sure how to recommend it to anyone. Except for this: even with the complex story and layered structure, Palmer somehow manages to bring it all seamlessly together in the end and leaves me wanting for the sequel - which, luckily, is already available. It also makes me think, an I hope the sequel does the same.